con <- DBI::dbConnect(RPostgres::Postgres(),

host = "aabc.b.db.ondigitalocean.com",

dbname = "db",

user = "db",

password = "abc123",

port = 25060)Shiny apps are R’s answer to building interface-driven applications that help expose important data, metrics, algorithms, and more with end-users. However, the more interesting work that your Shiny app allows users to do, the more likely users are to want to save, return to, and alter some of the ways that they interacted with your work.

This creates a need for persistent storage in your Shiny application, as opposed to the ephemeral in-memory of basic Shiny applications that “forget” the data that they generated as soon as the application is stopped.

Relational databases are a classic form of persistent storage for web applications. Many analysts may be familiar with querying relational databases to retrieve data, but managing a database for use with a web application is slightly more complex. You’ll find yourself needing to define tables, secure data, and manage connections. More importantly, you might worry about what things that you do not know you should be worrying about.

This post provides some tips, call-outs, and solutions for using a relational database for persistent storage with Shiny. In my case, I rely on a Shiny app built with the golem framework and served on the Digital Ocean App platform.

Databases & Options for Storage

Dean Attali’s blog post on persistent storage compares a range of options for persistent storage including databases, S3 buckets, Google Drive, and more.

For my application, I anticipated the need to store and retrieve sizable amounts of structured data, so using a relational database seemed like a good option. Since I was hosting my application on Digital Ocean App Platform, I could create a managed Postgres database with just a few button clicks. As I share in the “Key Issues” section, this solution offers some significant benefits in terms of security.

For more information on different options for hosting Shiny apps and some insight into why I chose Digital Ocean, check out Peter Solymos’ excellent blog on Hosting Data Apps.

Talking to your database through Shiny

General information on working with databases with R is included on RStudio’s excellent website. Below, I focus on a few topics specific to databases with Shiny, Shiny apps built in the {golem} framework, and Shiny apps served on Digital Ocean in particular.

Creating a database

To create a database for my application in DigitalOcean, I simply went to:

Settings > Add Component > Database

This creates a fully-managed Postgres databases so you do not have to thing a ton about the underlying set-up or configuration.

At the time on writing, I was able to add a 1GB Dev Database for /$7 / month. For new users, DigitalOcean offers a generous number of free credits for use in the first 60 days. For a more mature product, one can add or switch to a production-ready Managed Database.

After a few minutes, the database has launched and its Connection Parameters are provided, which look something like this:

host : abc.b.db.ondigitalocean.com

port : 25060

username : db

password : abc123

database : db

sslmode : requireBy default, the Dev Database registers your application as a Trusted Source, meaning that only traffic from the application can attempt to access the database. As the documentation explains, this type of firewall improves security by preventing against brute-force password or denial-of-service attacks from the outside.

Note: If you just want to experiment with databases and Shiny but aren’t using an in-production, served application, you can mostly skip this step and use the “Dev” approach that is discuss in “Dev versus Prod” subsection of “Key Issues” below.

Connecting to the database

We can use the connection parameters provided to connect to the database using R’s DBI package.

We will talk about ways to not hardcode one’s password in the last section.

Creating tables

Next, you can set up tables in your database that your application will require.

If you know SQL DDL, you can write a CREATE TABLE statement which defines a tables names, fields, and data types. However, this can feel verbose or uncomfortable to analysts who mostly use DML (e.g. SELECT, FROM, WHERE).

Fortunately, you can also define a table using R’s DBI package. First, create a simple dataframe with a single record to help R infer the appropriate and expected data types. Then pass the first zero rows of the table (essentially, only the schema) to DBI::dbCreateTable().

df <- data.frame(x = 1, y = "a", z = as.Date("2022-01-01"))

DBI::dbCreateTable(con, name = "my_data", fields = head(df, 0))To prove that this works, I show a “round trip” of the data using an in-memory SQLite database. Note that this is not an option for persistent storage because in-memory databases are not persistent. This is only to “prove” that this approach can create database tables.

con_lite <- DBI::dbConnect(RSQLite::SQLite(), ":memory:")

df <- data.frame(x = 1, y = "a", z = as.Date("2022-01-01"))

DBI::dbCreateTable(con_lite, name = "my_data", fields = head(df, 0))

DBI::dbListTables(con_lite)[1] "my_data"DBI::dbReadTable(con_lite, "my_data")[1] x y z

<0 rows> (or 0-length row.names)But where should you run this script? You do not want to put this code in your app to run every time the app launches, but we just limited database traffic to the app so we cannot run it locally. Instead, you can run this code from the app’s console. (Alternatively, if you upgrade to a Managed Database, I believe you can also whitelist your local IP as another trusted source.)

Forming the connection within your app

Once your database is set-up and ready to go, you can begin to integrate it into your application.

I was using the golem framework for my application, so I connected to the database and made the initial data pull by adding the following lines in my top-level app_server.R file.

con <- db_con()

tbl_init <- DBI::dbReadTable(con, "my_data")The custom db_con() function contains roughly the DBI::dbConnect() code we saw above, but I turned it into a function to incorporate some added complexity which I will describe shortly.

Most of the rest of my application uses Shiny modules, and this connection object and initial data pull can be seamless passed into either.

To see similar code in a full app, check out Colin Fay’s golemqlite project on Github.

CRUD operations

CRUD operations (Create, Read, Update, Delete) are at the heart of any interactive application with persistent data storage.

Interacting with your database within Shiny begins to look like more rote Shiny code. I do not describe this process in much detail since it is quite specific to what your app is trying to accomplish, but this blog post provides some nice examples.

In short:

- To add records to the table, you can use

DBI::dbAppendTable() - To remove records from the table, you can construct a

DELETE FROM my_data WHERE <conditions>statement and run it withDBI::dbExecute()

Some cautions on the second piece are included in the “Key Issues” section.

Key Issues

Adding a permanent data store to your application can open up a lot of exciting new functionality. However, it may create some challenges that your typical data analyst or Shiny developer has not faced before. In this last section, I highlight a few key issues that you should be aware of and provide some recommendations.

Securing data transfer

Already, we have one safeguard in place for data security since our application is the only Trusted Source able to interface with our database.

But, just like we secure our database credentials, it becomes important to think about securing the database itself. This is made easy with DigitalOcean because data is end-to-end encrypted, but depending on how or by whom your data is managed, this is something to bear in mind.

Securing database credentials

No matter how safe the data itself is, it still may be at risk if anyone can obtain our database credentials.

Previously, I demonstrated how to connect to a database from R like this:

con <- DBI::dbConnect(RPostgres::Postgres(),

host = "aabc.b.db.ondigitalocean.com",

dbname = "db",

user = "db",

password = "abc123",

port = 25060)However, you should never ever put your password in plaintext like this. Instead, you can use environment variables to store the value of sensitive credentials like a password or even a username like this:

con <- DBI::dbConnect(RPostgres::Postgres(),

host = "aabc.b.db.ondigitalocean.com",

dbname = "db",

user = "db",

password = Sys.getenv("DB_PASS"),

port = 25060)Then, you can define that same environment variable more securely in within the App Platform.

Securing input integrity (SQL injection)

Finally, it’s also important to be aware of SQL injection to ensure that your database does not get corrupted.

SQL injection is usually discussed in the concept of malicious attacks. For example, W3 schools shows the following example where an application could be tricked into providing data on all users instead of a single user:

txtUserId = getRequestString("UserId");

txtSQL = "SELECT * FROM Users WHERE UserId = " + txtUserId;If the entered UserId is "UserId = 105 OR 1=1", then the full SQL string will be "SELECT * FROM Users WHERE UserId = 105 OR 1=1;".

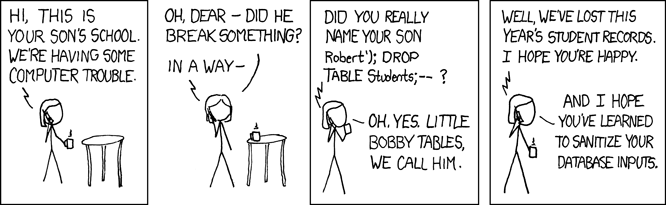

SQL injection is also at jokes you make have heard about “little Bobby Drop Tables” (xkcd).

That joke also, in some odd way, highlights that SQL injection need not be malicious. Rather, whenever we have software opened up to users beyond ourselves, they will likely use it in unexpected ways that push the system to its limit. For example, a user might try to enter or remove values from our database with double quotes, semicolons, or other features that mean something different to SQL than in human parlance and corrupt the code. Regardless of intent, we can protect against bad SQL that will break our application by using the DBI::sqlInterpolate() function.

A demonstration of this function and how it can protect against bad query generation is shown in this post by RStudio.

Dev versus Prod

However, you may have realized a flaw in this approach. Our entire app now depends on forming a connection that can only be made by the in-production app. This meams you cannot test your application locally. However, even if our local traffic was not categorically blocked, we wouldn’t want to test our app on the production database and recklessly add and remove entries.

Instead, we would ideally have separate databases: one for development and one for production. Ideally, these would be the same type of database (e.g. both Postgres) to catch nuances of different SQL syntax and database operations. However, to keep things simpler (and cheaper), I decided to use an in-memory SQLite database locally.

To accomplish this, I wrapped my database connection in a custom db_con() function that checks if the app is running in development or production (using golem::app_prod() which in turn checks the R_CONFIG_ACTIVE environment variable) and connects to different databases in either case. In the development case, it creates an in-memory SQLite database and remakes the empty table.

(Another alternative to creating the database on-the-fly is to pre-make a SQLite database saved to a .sqlite file and connect to that. But for this example, my sample table is so simple, creating it manually takes a negligible amount of time and keeps things quite readable, so I left it as-is.)

db_con <- function(prod = golem::app_prod()) {

if (prod) {

con <- DBI::dbConnect(RPostgres::Postgres(),

host = "abc.b.db.ondigitalocean.com",

dbname = "db",

user = "db",

password = Sys.getenv("DB_PASS"),

port = 25060)

} else {

stopifnot( require("RSQLite", quietly = TRUE) )

con <- DBI::dbConnect(SQLite(), ":memory:")

df <- data.frame(x = 1, y = "a", z = as.Date("2022-01-01"))

DBI::dbWriteTable(con, "my_data", df)

}

return(con)

}Managing connections

So, you’ve built a robust app that can run against a database locally or on your production server. Great! It’s time to share your application with the world. But what if it is so popular that you have a lot of concurrent users and they are all trying to work with the database at once?

To maintain good application performance, you have to be careful about managing the database connection objects that you create (with DBI::dbConnect()) and to close them when you are doing using them.

If this sounds manual and tedious, you’re in luck! The {pool} package adds a layer of abstraction to manage a set of connections and execute new queries to an available idle collection. Full examples are given on the package’s website, but in short {pool} is quite easy to implement due to it’s DBI-like syntax. You can replace DBI::dbConenct() with pool::dbPool() and proceed as usual!